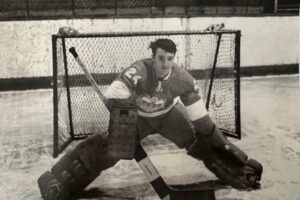

Roy Giesebrecht was best known as a hockey player, but when his country needed him, he chose the battlefields of Europe over his hockey career. It was the spring of 1942 and the war had been raging for three years when the 25 year old Giesebrecht handed in his Detroit Red Wings hockey jersey for a military uniform and an unknown future.

It was a bold move, but not an uncommon one. Several sporting figures had left their teams to join the allies in the battle against Nazi Germany, including Boston Red Sox slugger Ted Williams and Toronto Maple Leafs owner Conn Smythe, who had also served in the Canadian military in World War l. The decision would mean Giesebrecht would never play another game in the National Hockey League.

Assigned to the First Canadian Corps, Giesebrecht was stationed in Kingston, before he was sent to the East coast and then overseas, but before he left Canada, his family was jolted by tragedy. While spending Christmas at home before leaving for the Maritimes and then Europe, two of his sisters were seriously injured in a devastating train wreck in Almonte. A troop train had slammed into the back of a local passenger train while it was stopped at the Almonte station. Three dozen people had been killed and dozens more injured.

Assigned to the First Canadian Corps, Giesebrecht was stationed in Kingston, before he was sent to the East coast and then overseas, but before he left Canada, his family was jolted by tragedy. While spending Christmas at home before leaving for the Maritimes and then Europe, two of his sisters were seriously injured in a devastating train wreck in Almonte. A troop train had slammed into the back of a local passenger train while it was stopped at the Almonte station. Three dozen people had been killed and dozens more injured.

Upon learning of the crash, Giesebrecht drove from his parent’s home in Petawawa where the greater Giesebrecht clan had gathered for the holidays to Almonte to try to find his siblings. Jean O’Brien and Hilda Raby had survived, but Jean’s husband, Harold O’Brien and the couple’s two-year old son, Jackie, had been killed. Jean would spend months in hospital. Hilda would be hospitalized for a year and would never fully recover from having her legs crushed in the crash.

Almost two years after enlisting in the Canadian Armed Forces, Roy Giesebrecht boarded onto a ship bound for England where he was assigned to drive maintenance and supply trucks to move equipment and food to troops who were deployed in war torn regions. Deployed to France and then to the Netherlands, Giesebrecht was part of the Canadian force that liberated Holland, helping to arrest German soldiers who remained in the Dutch cities, but more importantly providing humanitarian aid to local residents, some of whom were near starving to death.

The Canadians were treated like heroes. They were the saviours for people who had been oppressed as their country was overtaken by German troops who in the latter part of the war cut off food supplies leading to thousands of the Dutch dying from mal-nutrition and starvation. While there, Giesebrecht made new friends. He lived for a few weeks with a family in the Netherlands, while he and other Canadian soldiers did what they could to help the Dutch get back on their feet.

In letters to his wife Teresa, Giesebrecht wrote about some close calls he had during the war. Stories of swimming in rivers where bodies of dead soldiers were floating or near misses under enemy gunfire while driving military vehicles were shared, but usually he asked how things were at home? In one letter written on July18, 1944, he wrote, “There was a bomb dropped a couple of hundred yards from me the night before last and it killed a few civilians and a few others were injured. You should have seen me get into my truck. I started before the bomb hit when I heard it whistle after the plane dropped it.”

In letters to his wife Teresa, Giesebrecht wrote about some close calls he had during the war. Stories of swimming in rivers where bodies of dead soldiers were floating or near misses under enemy gunfire while driving military vehicles were shared, but usually he asked how things were at home? In one letter written on July18, 1944, he wrote, “There was a bomb dropped a couple of hundred yards from me the night before last and it killed a few civilians and a few others were injured. You should have seen me get into my truck. I started before the bomb hit when I heard it whistle after the plane dropped it.”

His letters home would arrive by air mail, having been reviewed by the Canadian government censors to ensure they didn’t breach national security. He was never permitted to say where he was, but in that same summer of 1944 when the fighting had intensified, he asked his wife about his sister Hilda who was still recovering from her injuries in the train wreck. He wrote, “How is Hilda’s leg coming along? I hope she can get it fixed soon so she can get around well.”

In the final months of the war, Giesebrecht was on the move a lot. “We are about ready to move again. All we do is move these days, but I guess the more we move, the faster the war will be over,” he told his wife. As the allies pushed the German lines back, the Third Reich was collapsing but still fighting.

“There was a big battle going on yesterday morning while I was on guard duty. There were thousands of planes going over dropping their bombs and coming back over us. The sky was filled with bombers and often they finished the artillery, opened up all around us. What a racket and before it started the sun was shining bright as could be and then smoke filled the air and we could not see the sun for about three hours.”

Giesebrecht was a descriptive writer. His letters must have worried his wife sick as he described with great detail the sound of the bombs landing around him, the close calls and the deaths of fellow soldiers. It may be the reason Teresa Giesebrecht penned 836 letters to him, often writing several letters on the same day, praying that her letters would prompt him to write back so she knew he was okay. In a notebook, Teresa recorded the dates that she wrote her letters and she kept the more than 100 letters that her husband wrote her. They remain in the possession of her daughter Jane, but Teresa’s letters never came home when Giesebrecht returned to Canada in November of 1945.

Giesebrecht was a descriptive writer. His letters must have worried his wife sick as he described with great detail the sound of the bombs landing around him, the close calls and the deaths of fellow soldiers. It may be the reason Teresa Giesebrecht penned 836 letters to him, often writing several letters on the same day, praying that her letters would prompt him to write back so she knew he was okay. In a notebook, Teresa recorded the dates that she wrote her letters and she kept the more than 100 letters that her husband wrote her. They remain in the possession of her daughter Jane, but Teresa’s letters never came home when Giesebrecht returned to Canada in November of 1945.

After being discharged from the military, Giesebrecht could have returned to the Detroit Red Wings. He didn’t feel he was in shape to play in the best hockey league in the world and because the salaries were supressed by team owners, he chose to stay at home and help the Pembroke Senior Lumber Kings chase an Allan Cup championship while he worked in his family’s thriving grocery and distribution business.

By the time the Pembroke Memorial Centre opened in the fall of 1951 as a memorial to the region’s war dead, Giesebrecht was ready to hang up his skates for good. He was convinced to play one more season as the new rink was christened. At the end of the season, the Pembroke fans honoured his great hockey career with a special Roy Giesebrecht night. It was a fitting tribute to a man who put his country first, risking his life by voluntarily signing up for military service to ensure Canadians and people around the world would have freedom.

Roy Giesebrecht was a special hockey player but his legacy extends well beyond his ability to score goals. Like millions of Canadians, he was courageous and answered the call to duty when his country was at war. On Remembrance Day, that’s how we should remember Roy Giesebrecht, as a great Canadian who made a difference in the world. He was a soldier, and a darn good hockey player too.